Br. John Aidan Cook was buried here at Pluscarden on Saturday 6th December. He was not a monk of our house, though he had spent time trying his vocation with our community in 2018.

Br. John/Aidan had first tried his vocation with the Benedictine monks of Norcia in Italy. While still a Junior, both physically and mentally he found himself unable to continue on there. He came here in 2018 to see if he could live this vocation at Pluscarden. Although this also was not to be his path, he remained thereafter in close touch with the Pluscarden community, and was a regular guest. As a matter of fact he spent the whole first covid lock-down here.

Aidan then spent time living as a single lay man at his home at Crieff in Perthshire. After a cancer diagnosis, he went through the normal process of chemo-therapy, which at first seemed successful enough. But then the cancer became very aggressive and widespread, and he was advised that further treatment was pointless. He moved into the MacMillan Palliative Care unit at the Perth Royal Infirmary, where he was extremely well looked after.

Then on Tuesday 4th November, at Aidan's request, Abbot Benedict Nivakoff with Br. Peter came from Norcia to receive his solemn vows as a Benedictine monk. He managed to go home to nearby Crieff for that ceremony, although by then he could not stand without assistance. He took the name he had had while at Norcia, Br. John. After that, several Pluscarden monks travelled down to see him, and to offer Holy Mass at his bed side. That was an edifying and beautiful experience, because Br. John/Aidan was found to be completely happy, and at peace: strong in faith and hope; quite without fear, and without sadness or anger; deeply grateful for the love and support of his family and friends, for the wonderful medical care he received, and for the sacramental and pastoral ministrations of the Church.

He died on Tuesday 25th November 2025, aged only just 38.

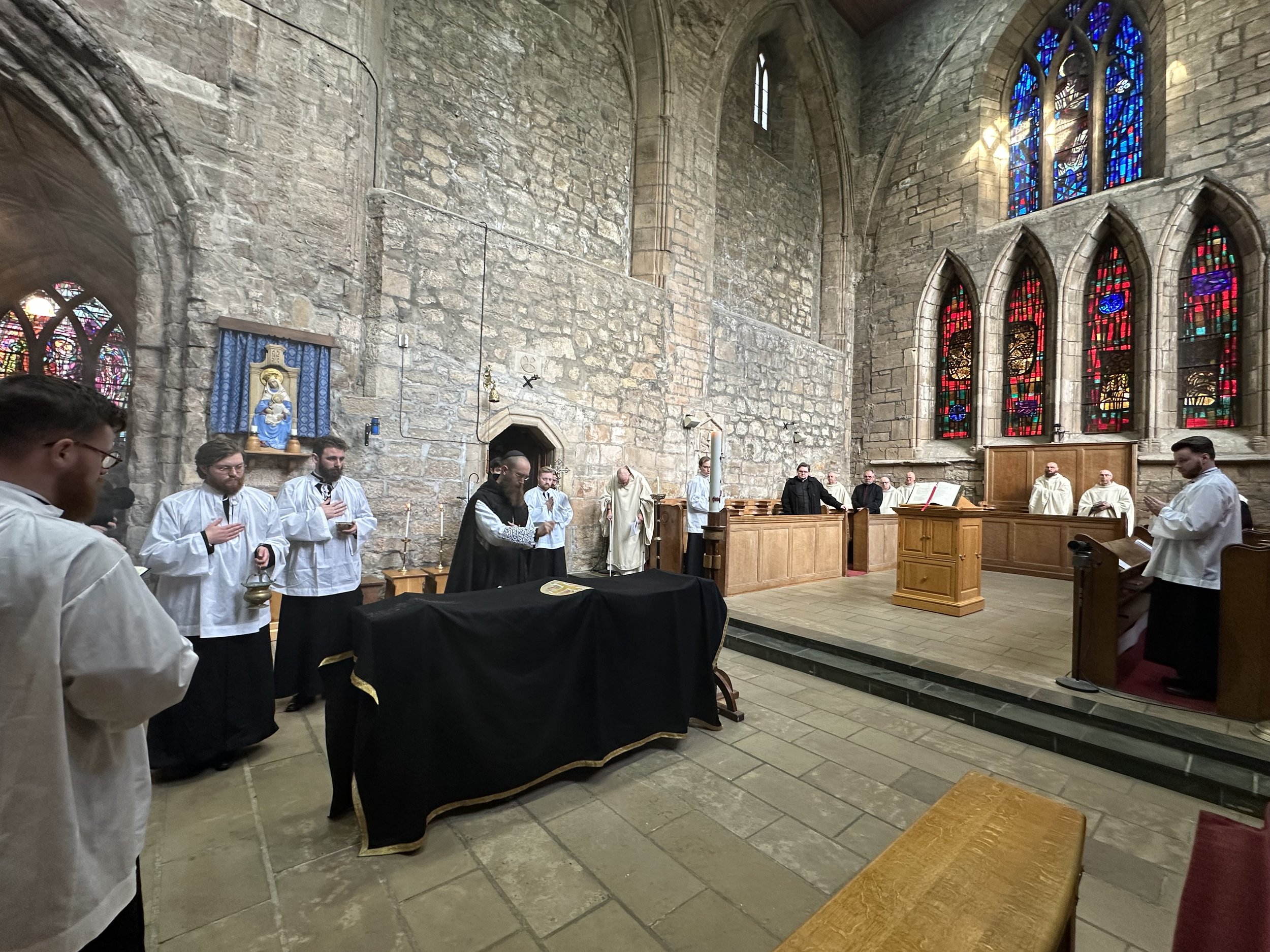

He asked to be buried at Pluscarden, and for his friends from the Confraternity of St. Benedict to be allowed to serve the liturgy. That request being granted, he landed up having a full monastic funeral. Indeed his funeral was certainly something to be remembered by all who participated!

Knowledge that he would be buried in our cemetery gave Br. John/Aidan great consolation in his final days. As he said: “I will be laid to rest in a place I love, where I have found peace, and where I will be surrounded by the prayers of the brethren."

Our Church was packed for the funeral, with large numbers of young families with small children being present. Prior Simon presided for the funeral Mass; Abbot Benedict preached, and then took over for the burial ceremonies. The nine servers we had for that were all former members with Aidan of Glasgow University, and the Catholic Chaplaincy there. Their contribution certainly made a significant difference to the solemnity of the occasion.

Requiem Mass for Br. John Aidan Cook, O.S.B.

Sermon

6 December 2025

Abbot Benedict Nivakoff, OSB

Lord, if you had been here, my brother would not have died.

The scene is a familiar one to us. Lazarus was Christ’s friend, a close and intimate friend. He knows that Lazarus is sick, that he will likely die and he delays visiting him, knowing also, as Christ always does, what is best, what will happen, how things will ultimately turn out. Lazarus will die, and Christ will bring him back to life, literally out of the tomb, thus accomplishing a miracle so great that the Pharisees will decide, with that quantity of stupidity of which only we, the clergy, seem completely capable, that they must kill Christ. Can he who raised Lazarus from the dead not come back to life himself?

The distance then – the space, the time, between Lazarus’ death and Lazarus being brought back to life – a space and time where we might ask, Where was Lazarus’ soul? Where was he? And we can ask and of course we can’t answer. This distance we can somehow see was such – was so small, was so thin – that it was breachable, at least by the God-made-Man, who came here we are to believe so that all might know God as Father, all might eventually come to rest. He is the Resurrection and He brings about this Resurrection. He reached through that tomb and brought Lazarus back to life.

To many outside Christian life, and perhaps to some of the more questioning within Christian life, there is a bit of absurdity to all this. It is a very nice story, but did Lazarus’ resurrection really happen? Did Christ’s? Questions left for an Oxbridge debate, one might argue, and not for a funeral Mass? Perhaps… perhaps if it weren’t for the fact that this Requiem is for a man, a monk, Aidan Cook, who entered the debate, who made his voice heard in so many ways.

Whether we want to believe that Lazarus and Christ really rose or not, we would be rather blind not to accept that Christians have thought so for two thousand years, and that some of those early Christians thought so to such an extent that they wrote it down and formed their lives based on what they believed to be true. They even went to brutal deaths in defence of this. Can any of us really doubt this? No, these are historical facts, and there are witnesses to this fact from every age, telling us, at times with an austere Romanesque murmur, at other times with a discreet Gothic whisper, and then again with a proud Baroque trumpet – every age has said this is true.

Brother John said this too. Yes, of course he said this in his sincere seeking of the truth, in his fight in defence of the suffering – against legalized euthanasia – in his fine love of art, in his gentle devotion to his family, in his subtle aesthetic sensibility, and in his carefully sparing use of the tongue (ah, the long silent pauses as we all waited for an answer which one expected would be three pages and could be only one word… “Yes”) … but today I do not refer to any of these.

For all of these are qualities that many people have. They were beautiful traits in him, and we loved him with them, and sometimes despite them.

What Brother John had, he himself esteemed quite little. Let us listen to him a moment, to what

he wrote a few weeks before his death – he whose body sits there before us and whose soul is…

somewhere quite near, as Lazarus’ was…

“My life thus far seems to be an accumulation of unfinished tasks and goals: an unfinished apprenticeship cabinet, a start on the mastery of drawing and painting, a half-hearted attempt to sell my artwork, a half-renovated house, a half-finished garden… the list goes on. And that is without mentioning an incomplete monastic vocation, an unfulfilled desire to be a priest, and a half-discerned new possibilities of a vocation. Suffice to say that I have not been good at completing things, at getting things done. I now have to find peace with the possibility of leaving most of them undone. At only 37, perhaps I shouldn’t be concerned that completion is yet to be found, but still, can I draw from these uncompleted tasks a complete life?”

As all of us lived and watched and participated in one way or another with what Aidan calls his “unfinished tasks” … were we disappointed in him? Did we pity him? Did we scorn him? I dare say no, we didn’t. But perhaps I am not the only one who, until only recently, could not say why this apparent lack of doing something didn’t bother us. For if we moderns value anything, it is getting something done, accomplishing at least something, being useful in at least one way… by his own estimation, this was not something he was able to do.

And yet… yet he did so much more. One month before he died, Aidan made vows as a monk of Norcia. Again, in his own words…

“My attempt at the monastic life did not end because of some revulsion to or alienation from the monastic ideal. It was simply that in my physical and mental state I found myself incapable of carrying on. Having begun to dwell on the similarity of serious illness and monastic life, I see how such vows could draw together both strands of my life, indeed the whole of my life. In fact, I think they could be the completion of an incomplete life, the fulfilment of all my unfinished tasks, my *consummatum est*.”

To Aidan, to Brother John, this was his ultimate gift to God. At his request, he died in his habit and will be buried in it. My own personal experience, however – and one that I must believe – is that also of his very devoted brothers and sisters, his unflagging mother, his family, the loyal confraternity, his friends, and the faithful monks of Pluscarden, who so graciously welcomed him time and again and even now in their cemetery… is that Br John did one thing more, one thing that so many priests and religious, so-called holy people, cannot do, with our holy words, our clever sermons… he gave us Hope.

Hope is stronger than proof, and often more powerful even than love. Sometimes love is there, but we cannot summon it; we cannot even see it without hope. Hope feeds love by reminding us of the end, God who is Love, a love of which ours is just a pale imitation. Aidan looked at death – he looked at every moment that led up to his death – with all the tasks that would remain unfinished, all the supposed uselessness… as an occasion to give this to us, to give us hope. He writes:

“I spoke to Br. Peter yesterday and he mentioned again his trip to Iona and the idea of its being a thin place, where the boundary between heaven and earth is particularly narrow, and that death does something similar. What a beautiful thought, that the dying person is a thin place where the veil is drawn aside and heaven becomes close to all who approach! I see this now as my mission: to be a thin place where those around me, whether family, friends, carers or strangers, can see through the burden of illness to the beauty and joy of heaven, can see through the trials of this earthly human life to the glory of God and his unfailing, abundant love.”

Anyone can talk about these things, but only a man with death right before him can do so, socredibly that he inspires hope in those around him. Like a silly priest, I asked him at one point, Do you ever ask, “Why me?” His answer was an icon of how he lived: the question hadn’t even occurred to him.

Aidan, Brother John, and I – like many of you, no doubt – shared a common love for that cult classic British Catholic novel, Brideshead Revisited. We both saw how much he resembled the serially detached Charles Ryder, whose own path to love, to God, passed through poverty and wealth, hatred and adultery, death and life, and through a newfound hope in a God he didn’t want to acknowledge could be there. In Brother John’s several attempts to become a monk, in his various so-called unfinished works, I think of the wounded Charles’ words: “Thus I returned to Paris, and to the friends I had found there, and the habits I had formed. I thought I should hear no more of Brideshead, but life has few separations as sharp as that.”

Life has few separations as sharp as that. Aidan thought his last great work was his monastic profession. What he must, in some mysterious way, realize now, as his soul lingers with us from the other side of the thin place, is that he has helped us to see something: his thin place lived at the end but in many ways lived throughout his whole life, has given us hope in a world that is unlike our own – a world we don’t need to prove, but which only asks us not to say “no.”

One last word from him before I close:

“For years, a daily prayer of mine has been another line of St. John Henry Newman, ‘I ask not to see - I ask not to know - I ask simply to be used.’ It seems that this is how he has chosen to use me, and I thank God that he has.”

You have been used, dear Aidan. And you have brought us great Hope. Please continue to do that. In your death you have taught us to hope. May you now have rest.